Death in the Victorian Era

The Victorian Era was a golden age for literature, culture, and the arts. However, strange quirks and odd traditions emerged alongside the industrial revolution. From the obsessions around mourning to the beginnings of Victorian spiritualism, the world of death and the beyond was a topic that captivated Victorian culture and traditions.

Dead Men Smiling

For a time, Victorians reserved death portraits for prominent people. But that soon changed. Creating a death portrait in the home during the mourning period became fashionable. The original mourning portraits were expensive and reserved for the upper-middle-class as photography had yet to advance. However, with the invention of the Daguerreotypes, those with limited income could also create an image of their deceased loved ones.

Daguerreotypes were remarkably detailed photographic images exposed onto a silver-plated sheet of copper. First developed in mercury fumes, the sheets were then stabilised with salt water, resulting in a clear picture. This process required a subject to remain still for a time, though less time than photography had once taken. Usefully, the dead tend not to move, so it was a logical step for mourning families to use this method for their portraits.

Hand-held Daguerreotypes were popular for parents of deceased youngsters who may not have taken their image in life. The photograph often showed the child lying in bed as if asleep. As the era progressed, including the bereaved parents became common. The trend varied for adults, often arranging the deceased subject to appear as lifelike as possible. This might involve the subject sitting upright or standing in the parlour. Many families would join their deceased loved ones in the image, ensuring a focus on remembrance rather than sadness.

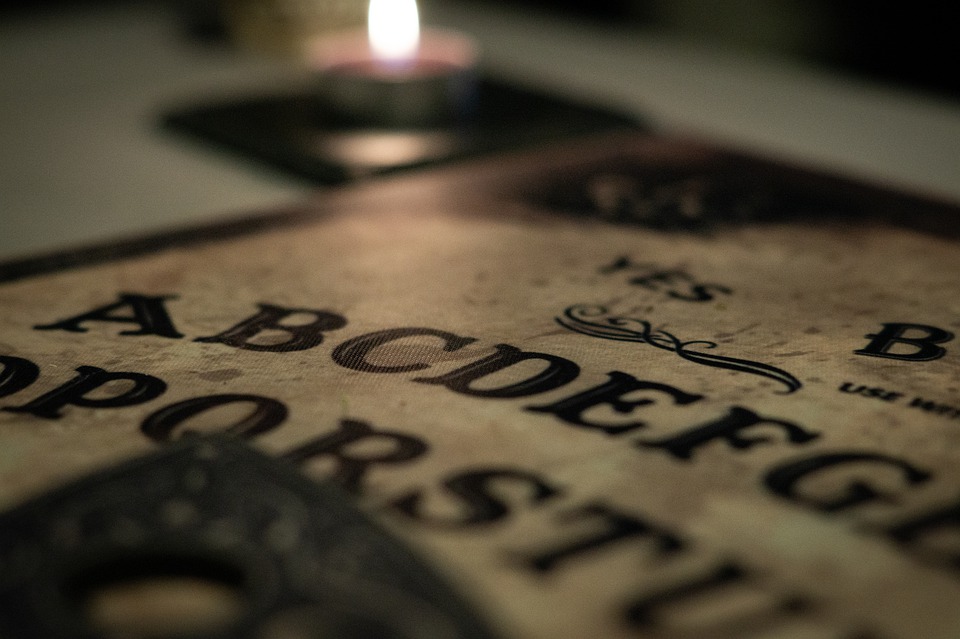

Communication With The Other Side

During this period, the Fox sisters gained prominence. Leah, Maggie, and Kate Fox claimed a resident ghost named Mr Splitfoot would respond to their questions by rapping on the floorboards. Their story became popular, leading them to take their performances on tour, conducting seances for a paying audience in Corinthian Hall, Rochester. However, their supposed supernatural abilities were proven a hoax. The sisters had tapped their feet against the table beneath their voluminous dresses.

Spiritualism fascinated the author Arthur Conan Doyle, but Charles Dickens remained unconvinced, satirising his cynicism in The Christmas Carol.

Returning From the Dead?

As science and the Scientific Method spread throughout Victorian England, so did the central idea of resurrection. In fact, the study of the body, its limits, and how to heal it became a strong focus for many gentlemen, medical practitioners and scientists. Following the first successful blood transfusion in 1818, Blundell used his knowledge and experience to complete the first whole blood transfusion in 1840, helping treat a patient’s haemophilia. Soon after, in 1884, saline was introduced as a blood replacement, taking over from milk, a treatment we still use today. Unfortunately, successful experiments were not typical. Many theories missed the mark or came closer to mad science than medicine, like galvanisation. This process created electrical signals through chemical reactions by shocking something with electricity to get a result. After Luigi Galvani’s shows involving electricity used to stimulate the muscles of dead frogs and other animal carcasses, several theories considered electricity the key to resurrection. Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein also inspired some of these ideas with her creation of Frankenstein. Sadly, Victorian scientists never realised their dream of resurrection.

Despite the strange customs of the Victorians, some of their ideas and methods are still in use today, though vastly changed over the years. The advances in medicine and understanding have been incorporated and improved in the modern day, allowing us to utilise blood transfusions, skin grafts and more. Many ideas from the spiritualism movement appear in today’s writing world, inspiring everything from possession stories to tales of the walking dead. Thankfully, we have phased out the concept of photographing our dead post-mortem, which could have led to a rather esoteric social media trend.

Guest Article by Alexander Fairweather