Located a short way along the Shotley peninsula, the village of Chelmondiston is notable for the hamlet of Pin Mill and views across the River Orwell. Rebuilt in the 1860’s, the local parish church of St Andrews lost its tower to a flying bomb in 1944. But it was the Chelmondiston Rectory that was the subject of interest in a Bury & Norwich Post article during November 1890.

Located a short way along the Shotley peninsula, the village of Chelmondiston is notable for the hamlet of Pin Mill and views across the River Orwell. Rebuilt in the 1860’s, the local parish church of St Andrews lost its tower to a flying bomb in 1944. But it was the Chelmondiston Rectory that was the subject of interest in a Bury & Norwich Post article during November 1890.

My books are themed, and The Ripper Deception explores the Victorian fascination with spiritualism. Before its conclusion in London, Violet and Lawrence embark on different investigations with Violet arriving in Chelmondiston to find out the cause of strange noises in the Rectory. Her visit coincides with one by a representative of the Society for Psychical Research.

I based this part of The Ripper Deception on the Bury & Norwich post article which described the haunting in detail. The Rectory, standing on the left of the road running from Ipswich to Shotley, was built around 1850 and was home to several rectors before the arrival of the Reverend George Woodward and his wife, Alice. The previous Rector, the Reverend Beaumont, had a large family but the Reverend and Mrs Woodward were childless, and the household was considerably quieter. When they first moved to the house, they were unaware of its reputation, but before long they began to hear footfalls in the passages and doors opening and closing in the dead of night. After speaking to the servants, it became apparent that they also witnessed unexplained noises, and one of the maidservants saw the ghost who she described as a small, shabbily-dressed, grey-bearded man.

The disturbances continued unabated with the Reverend concerned enough to search every nook and cranny of the house looking for an explanation. He examined drains, removed floorboards and even inspected the ivy on the outside walls, but the noises and sightings continued. The newspaper reported that a member of the Psychical Society arrived to instigate personal inquiries but heard nothing unusual. Neither did several gentlemen of the neighbourhood who also watched at night.

Nevertheless, rumours of the ghost spread into the village and reached the ears of the older inhabitants. They still remembered Reverend Beaumont’s predecessor, a certain Reverend Richard Howarth who was Rector of the parish from 1858 until his death from acute bronchitis in 1863. Reverend Haworth was an inveterate miser, so mean that he dressed in rags and only allowed himself half an egg for a meal. He became known as “cabbage” Haworth after promising an ill parishioner a treat and delivering a cabbage.

But why would a miserly man of religion haunt the Rectory? Those who remembered Reverend Haworth also recalled the unusual circumstances of his will. Buried in the Chelmondiston churchyard, Howarth was worth about £40,000 when he died, and his will was supposedly found in a pond near the roadside in a book of old sermons wrapped in a piece of cloth. Villagers believed that his troubled spirit still searched the rectory for some hidden portion of his money.

The story sounds unlikely, but a quick look at the 1861 census shows the Reverend living at the Rectory with one servant. He died a bachelor on 7th February 1863 and letters of administration granted personal estate and effects to his brother George. So far, so good. However, an article in the Cambridge Independent Press on 23 May 1863 describes a court case resulting when an anonymous letter containing the missing will turned up at the home of his relative James Haworth. The will, drawn up and executed by the Reverend Haworth’s nephew Richard was partly burned and torn. The judge viewed the will with great suspicion, as there was no indication of how it got burned, and whether the damage constituted cancellation. He postponed the case with instructions that it could not proceed without the collection of further evidence. And that’s where my investigation ends. I can’t find any other articles to prove what happened next.

However, an 1884 newspaper cutting shows a list of large, unclaimed fortunes, one of which is in the name of Haworth. Mysteriously, the final paragraph of the Bury & Norwich Post article explains the lack of progress in the case stating that the judge who tried the issue died suddenly at the most critical point. This is true – he did. Justice Cresswell died in office on 29 Jul 1863 from complications arising from a fall from his horse.

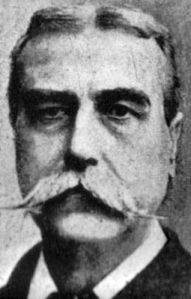

In June 1888 a tall, moustached man arrived at the Cricketers Inn, Black Lion Street, Brighton suffering from neurasthenia (intense fatigue). A holiday in the popular Sussex seaside resort must have seemed like the perfect antidote to his ailments. A student of the occult sciences, Roslyn Donston may well have occupied his convalescence in Brighton by furthering his knowledge of black magic and esoteric doctrines. Or, according to some, he may have been planning a series of murders in Whitechapel.

In June 1888 a tall, moustached man arrived at the Cricketers Inn, Black Lion Street, Brighton suffering from neurasthenia (intense fatigue). A holiday in the popular Sussex seaside resort must have seemed like the perfect antidote to his ailments. A student of the occult sciences, Roslyn Donston may well have occupied his convalescence in Brighton by furthering his knowledge of black magic and esoteric doctrines. Or, according to some, he may have been planning a series of murders in Whitechapel.  Was Donston Jack the Ripper? Well, if the recent DNA testing of Catherine Eddowes’ shawl is correct, then clearly not. However, several leading geneticists have cast doubt over the provenance and contamination of the shawl, and there are issues (which I don’t pretend to understand) regarding mitochondrial DNA. The identity of the Ripper is by no means solved, and probably never will be.

Was Donston Jack the Ripper? Well, if the recent DNA testing of Catherine Eddowes’ shawl is correct, then clearly not. However, several leading geneticists have cast doubt over the provenance and contamination of the shawl, and there are issues (which I don’t pretend to understand) regarding mitochondrial DNA. The identity of the Ripper is by no means solved, and probably never will be.  On Friday 22nd June 1888 Edmund Gurney checked into the Royal Albion Hotel opposite the Aquarium on Brighton’s seafront. The hotel was an unusual choice for Mr Gurney. A frequent visitor to Brighton, he most commonly stayed in lodgings. Perhaps, this time, he craved the anonymity of a busy hotel. Gurney’s reason for being in Brighton was equally unclear. He had been summoned, by letter, but had not disclosed why, or by whom. His contact details were omitted from the hotel register, and he had no identification on his person, save for one unposted letter.

On Friday 22nd June 1888 Edmund Gurney checked into the Royal Albion Hotel opposite the Aquarium on Brighton’s seafront. The hotel was an unusual choice for Mr Gurney. A frequent visitor to Brighton, he most commonly stayed in lodgings. Perhaps, this time, he craved the anonymity of a busy hotel. Gurney’s reason for being in Brighton was equally unclear. He had been summoned, by letter, but had not disclosed why, or by whom. His contact details were omitted from the hotel register, and he had no identification on his person, save for one unposted letter.